Seeing God’s Face in the Hidden Years

- Sylvia Jeronimo

- Jun 16, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Jul 23, 2025

A heartfelt reflection on Henri Nouwen’s Adam: God’s Beloved while journeying through my mother’s dementia

I picked up Adam: God’s Beloved at a time when my heart was heavy and searching. My mom’s dementia has been one of the hardest realities I’ve ever had to face. I was longing for something—anything—that could help me see her situation with new eyes. I wanted a perspective that would give me hope, patience, and maybe even a sense of peace. This book ended up being exactly that gift.

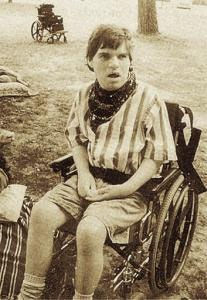

Henri Nouwen’s tender relationship with Adam, a young man who was severely mentally handicapped, spoke to me in ways I didn’t expect. Through Nouwen’s eyes, Adam became so much more than someone in need of care. He became a living reminder of the sacredness of life, of a human being sent by God with a unique mission—not through words or achievements, but simply through his being. And as I read, I realized how beautifully that translates to my mom’s journey with dementia.

What struck me most was how Nouwen describes people like Adam—and, by extension, those who are elderly, fragile, or living with dementia—as bearers of qualities we often lose in the rush of daily life: welcome, wonder, directness, and pure presence. They become, as Nouwen puts it, living reminders of the central values of the heart. Reading that, I felt as if a light had turned on in my own heart. My mom, in these hidden years of her life—years that are hidden from us and known fully only to God—is still bearing witness to God’s love, even in (or maybe especially through) her brokenness.

Nouwen’s words helped me see that in this vulnerable state, people like my mom are emptied of all the distractions, ambitions, and attachments that the rest of us cling to. And in that emptiness, God can fill them completely. But—and this is the hard part—we need eyes to see this hidden beauty. We need to be open to receiving the gift of their peaceful presence, because only what is received can be given. This idea—that the most hidden, the most fragile lives are often the most significant in God’s eyes—was both humbling and comforting.

What really moved me was Nouwen’s call to simply be with those who are vulnerable. People like my mom may not be able to trust their minds anymore, but they entrust their bodies, their presence, their very selves to us. And in that quiet trust, they seem to say, just be with me, and trust that this is where you have to be and nowhere else.

I’ll admit, that’s not easy. Being present to someone with dementia can make me feel vulnerable. It exposes my own insecurities and helplessness. But Nouwen gently reminds me that this radical vulnerability, this surrender, is the way of Jesus. Jesus fulfilled his mission not through action, but through passion—through what was done to him. And in my own small way, in simply being with my mom in her suffering, I am drawn into that same mystery.

There’s a deep truth here that I’m slowly learning to accept: when all is lost—when words fail, when memory fades, when roles reverse and I am the one holding steady—it is then that peace can speak to peace, and silence can dwell with silence. And in that space, God is present.

Henri Nouwen’s Adam didn’t give me easy answers or a roadmap. What it gave me was an invitation: to see my mom’s dementia not just as loss, but as a hidden blessing; not just as a burden, but as an opportunity to receive God’s love in a new way. It reminded me that care is not a one-way street.

There’s a mutuality in it—a chance for friendship, for presence, for grace.

If you’re walking through the valley of dementia with a loved one, or any kind of deep loss, I can’t recommend this book enough. It helped me begin to love my grief, to sit with it, and to trust that even in the darkness, we are held by the God who fashioned us by hand and calls us each beloved. And somehow, in telling my mom’s story, in living it alongside her, I can believe that morning will one day turn to dancing, and that this, too, is part of our eternal story.

We lose ourselves in books,

we find ourselves there too ~ anonymous

~Sylvia

Comments